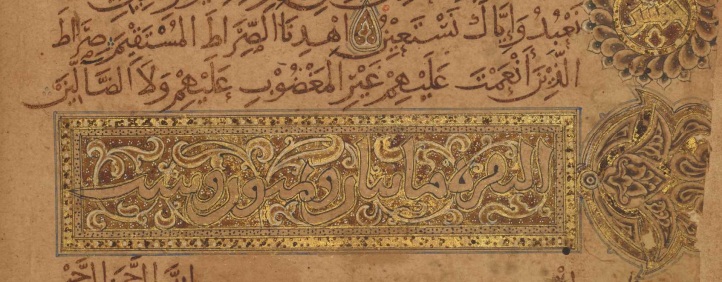

এই কুরআন শরীফটি ৩৯১ হিজরীতে লেখা হয়েছে। এটি লিখেছেনি আলী ইবনে হিলাল। যিনি ইবনুল বাওয়াব নামে পরিচিত। যার পুরো নাম আবু আল-হাসান আলী বিন হিলাল বিন আব্দুল আজিজ, (মৃত্যু 2 জুমাদা আল-আউয়াল 413 হি / 3 আগস্ট 1022 খ্রিস্টাব্দ) অন্যতম বিশিষ্ট আরবি ক্যালিগ্রাফার। তিনি বাগদাদে জন্মগ্রহণ করেন। ক্যালিগ্রাফার হওয়ার পাশাপাশি তিনি সাজসজ্জা ও অলঙ্করণের অনুশীলনও করতেন।

কুরআন মাজীদটি দেখুন এই লিংক থেকে: https://archive.org/details/mushaf-ibn-al-bawwab/mode/1up?view=theater

এই কুরআনের কপিটি আয়ারল্যান্ডের রাজধানী ডাবলিনের চেস্টার বিটি লাইব্রেরিতে (The Chester Beatty Library) সংরক্ষিত আছে।

এটি ডাবলিনের প্রসিদ্ধ যাদুঘর ও লাইব্রেরী।

The sole surviving Qur’an penned by Ibn al-Bawwab, housed at the Chester Beatty Library, is the earliest example of a paper-based Qur’an manuscript. Representing a transition from Kufic or semi-Kufic Qur’ans transcribed on parchment or vellum, the Chester Beatty manuscript is written fully in rounded, cursive script on paper.[7] Though the art of paper-making had arrived in Baghdad in the 9th century via the Silk Road, the thinner and more consistent texture of Ibn al-Bawwab’s manuscript indicates that the development of finer paper, worthy of transcribing God’s word, was a factor in the move from parchment to paper.[8]

The manuscript itself contains 286 folios and originally measured 14x19cm. Additionally, the text is fully vocalized with both vowels and consonants written in the same color ink. It is notable for its fine illumination, using the traditional blue, gold, and sepia on the main pages containing text and further incorporating brown, white, red and green in the opening and closing pages. Given Ibn al-Bawwab’s background, it is not surprising to find that the illumination was done by calligrapher himself, indicated in some sections by the use of a reed pen rather than a brush as well as the same ink used for the text.[9]

Apart from the use of paper, the Chester Beatty manuscript is notable for several innovations to Qur’anic calligraphy which heavily influenced the art for centuries. This paper Qur’an, unlike its parchment and vellum predecessors, was oriented vertically rather than horizontally.[10] Breaking from tradition, Ibn al-Bawwab’s Qur’an does not use the Kufic script which dominated Islam’s first three centuries, instead utilizing more legible cursive scripts. Naskh is used in the main text while the related thuluth script appears in the opening pages as well as the Sura headings and statistical pages containing verse-count. These statistical folios, which began to appear in the semi-Kufic Qur’ans preceding Ibn al-Bawwab, were here expanded to include additional information such as the total word and letter count of each Sura, the word count of the entire manuscript, and even the number of dotted and undotted letters.[11]

Two additional style innovations adopted by Ibn al-Bawwab involve spacing. Whereas previous calligraphers had used symmetrical spacing in the Bismala, Ibn al-Bawwab here relies upon asymmetry, extending one letter to create a large gap between words, drawing the reader’s eyes across the page and clearly demarcating a new section. With regard to his spacing of the verses, he left no spaces between individual verses, marking them instead with small, triangular clusters of blue dots. Every fifth and tenth verse, however, does include spacing which is filled with the standard gold markers.[12]

বিস্তারিত পড়ুন: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_al-Bawwab